|

|

|

LEGAL EAGLE EYE NEWSLETTER For the Nursing Profession Request a complimentary copy of our current newsletter What is our mission? What publication formats are available? How do I start a subscription? Can I cancel and get a refund? Does my subscription renew automatically? |

| WHAT IS OUR MISSION? |

| Our mission is to reduce nurses' fear of the law and to minimize nurses' exposure to litigation. Nurse managers need to spot potential legal problems and prevent them before they happen. Managers and clinical nurses need to be familiar with how the law is applied by the courts to specific patient-care situations, so that they can act with confidence. |

|

We work

toward our goals every month by highlighting the very latest

important Federal and state court decisions and new Federal

regulations directly affecting nurses in hospitals, long term care

facilities and home health agencies. We focus on nursing negligence

and nurses' employment and licensing issues.

|

|

WHAT PUBLICATION FORMATS ARE AVAILABLE? |

|

The Email

Edition is our most popular format.

You receive the newsletter as a PDF file attachment in an email

sent to you every month. On

any computer or mobile device you simply click the file attachment to

open, read, download, and/or print the newsletter. |

|

The Email

Edition is ideally suited to individuals.

It can also be used by large institutions.

Within an institution, like a hospital or university nursing

department, an individual subscriber can forward pertinent articles to

colleagues within the institution.

The content cannot be forwarded outside the institution or posted

online. An example

might be a nursing director or director of nursing education who shares

articles with nurse managers in individual clinical departments |

|

The Online Edition is a format suited to educational and healthcare

facility libraries with multiple users.

We send a link via email for the current monthly newsletter.

To open the link to the newsletter for that month the subscriber

or other user must be using a computer or device whose IP address or

range of IP addresses we have authenticated and given permission for

online access. |

|

Print, Email and Online

formats contain exactly the same content, eight pages with no

advertising. |

|

The links below go to secure online sites maintained for

us by Square, Inc. for credit and debit card purchases.

At checkout you will provide your name, payment information and email address. |

Email Subscription $120/year |

|

Print / Print + Email Subscription $155/year |

|

If you prefer, you can download and print an order form to mail

or to scan and email to us.

Checks, credit and debit cards, purchase orders accepted, or we will

bill you. |

|

CAN I CANCEL MY SUBSCRIPTION AND GET A REFUND? |

|

Yes. Just ask and the

unused portion of your subscription will be refunded. |

|

DOES MY SUBSCRIPTION RENEW AUTOMATICALLY? |

| No. Before your annual subscription runs out you will receive a renewal notice by email and regular mail. |

Legal Eagle Eye Newsletter

For the Nursing Profession

PO Box 1342 Sedona AZ 86339

(206) 718-0861

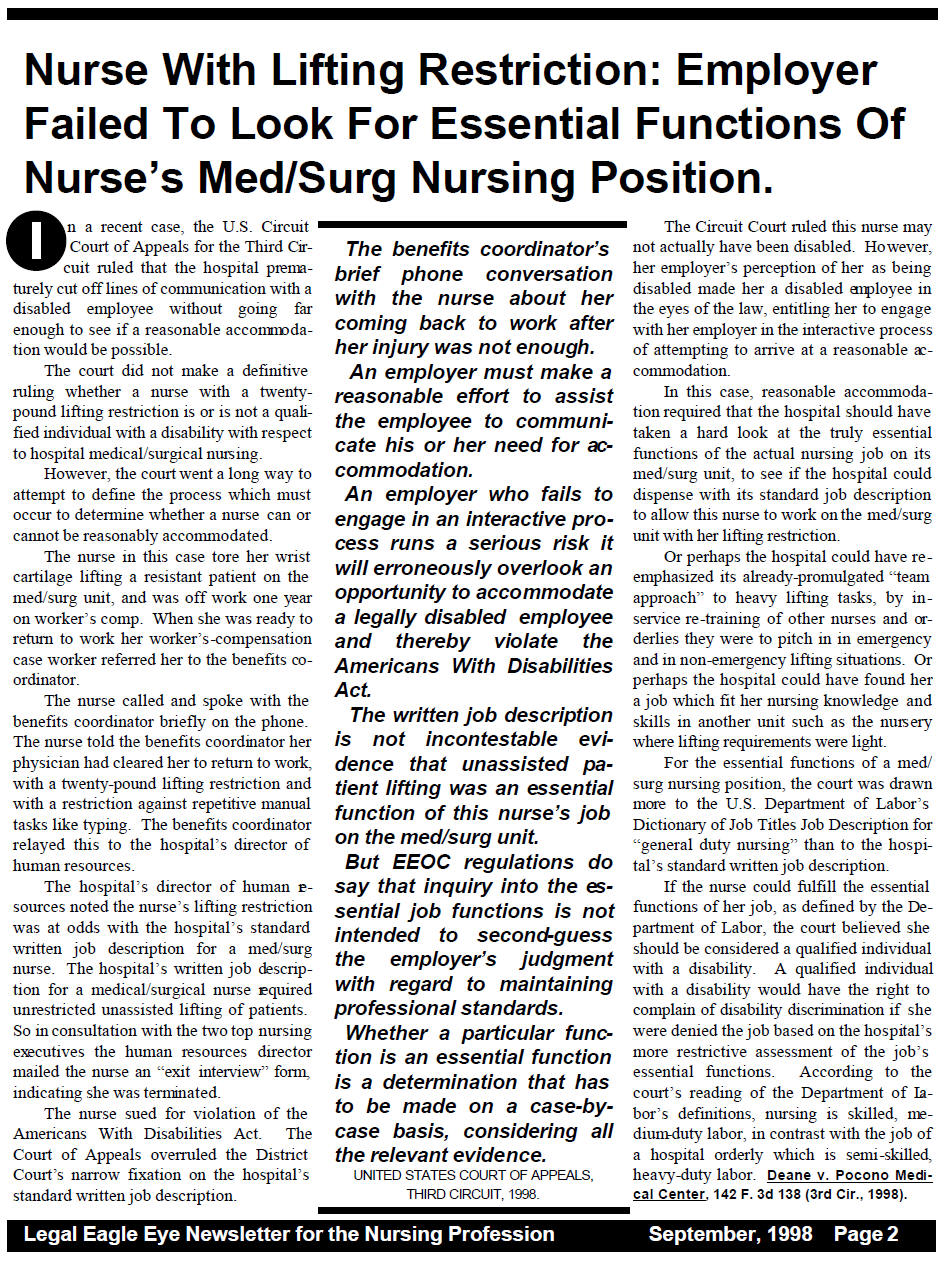

Quick Summary: An employer must make a reasonable effort to assist a disabled nurse to communicate his or her need for accommodation.

The benefits coordinator's brief phone conversation with the nurse about her coming back to work after her injury was not enough.

An employer who fails to engage in an interactive process runs a serious risk it will erroneously overlook an opportunity to accommodate a legally disabled employee and thereby violate the Americans With Disabilities Act.

The written job description is not incontestable evidence that unassisted patient lifting was an essential function of this nurse’s job on the med/surg unit.

But EEOC regulations do say that inquiry into the essential job functions is not intended to second-guess the employer’s judgment with regard to maintaining professional standards.

Whether a particular function is an essential function is a determination that has to be made on a case-by-case basis, considering all the relevant evidence.

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS, THIRD CIRCUIT, 1998. In a recent case, the U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals for the Third Circuit ruled that the hospital prematurely cut off lines of communication with a disabled employee without going far enough to see if a reasonable accommodation would be possible.The court did not make a definitive ruling whether a nurse with a twenty-pound lifting restriction is or is not a qualified individual with a disability with respect to hospital medical/surgical nursing.

However, the court did go a long way to attempt to define the process which must occur to determine whether a nurse can or cannot be reasonably accommodated.

The nurse in this case tore her wrist cartilage lifting a resistant patient on the med/surg unit, and was off work one year on worker’s comp. When she was ready to return to work her worker’s-compensation case worker referred her to the benefits coordinator.

The nurse called and spoke with the benefits coordinator briefly on the phone. The nurse told the benefits coordinator her physician had cleared her to return to work, with a twenty-pound lifting restriction and with a restriction against repetitive manual tasks like typing. The benefits coordinator relayed this to the hospital’s director of human resources.

The hospital’s director of human resources noted the nurse’s lifting restriction was at odds with the hospital’s standard written job description for a med/surg nurse. The hospital’s standard written job description for a medical/surgical nurse required unrestricted unassisted lifting of patients. So in consultation with the two top nursing executives the human resources director mailed the nurse an "exit interview" form, indicating she was terminated.

The nurse sued for violation of the Americans With Disabilities Act. The Court of Appeals overruled the District Court’s narrow fixation on the hospital’s standard written job description.

The Circuit Court ruled this nurse may not actually have been disabled. However, her employer’s perception of her as being disabled made her a disabled employee in the eyes of the law, entitling her to engage with her employer in the interactive process of attempting to arrive at a reasonable accommodation.

In this case, reasonable accommodation required, first of all, that the hospital should have taken a hard look at the truly essential functions of the actual nursing job on its med/surg unit, to see if the hospital could dispense with its standard job description to allow this nurse to work on the med/surg unit with her lifting restriction.

Or perhaps the hospital could have re-emphasized its already-promulgated "team approach" to heavy lifting tasks, by in-service re-training of other nurses and orderlies they were to pitch in in emergency and in non-emergency lifting situations. Or perhaps the hospital could have found her a job which fit her nursing knowledge and skills in another unit such as the nursery where lifting requirements were light.

For the essential functions of a med/surg nursing position, the court was drawn more to the U.S. Department of Labor’s Dictionary of Job Titles Job Description for "general duty nursing" than to the hospital’s standard written job description.

If the nurse could fulfill the essential functions of her job, as defined by the Department of Labor, the court believed she should be considered a qualified individual with a disability. A qualified individual with a disability would have the right to complain of disability discrimination if she were denied the job based on the hospital’s more restrictive assessment of the job’s essential functions. According to the court’s reading of the Department of Labor’s definitions, nursing is skilled, medium-duty labor, in contrast with the job of a hospital orderly which is semi-skilled, heavy-duty labor.

Deane v. Medical Center, 142 F. 3d 138 (3rd Cir., 1998).